In the world of board games, there’s something magical about discovering a hidden gem. A small-box wonder from a distant convention, a quirky design that challenges everything you thought you knew about gameplay, or a handmade creation born from pure creative passion rather than commercial ambition. Today, we’re diving into this fascinating underground with Ben from Travel-Games, a curator of the unusual and champion of the undiscovered who’s dedicated his work to bringing these extraordinary games to UK players.

From the bustling aisles of Tokyo Game Market to the DIY spirit of indie designers worldwide, Ben’s journey reveals a vibrant ecosystem of creativity that exists far beyond the mainstream gaming landscape. In this conversation, we explore how cultural differences shape game design, what it takes to import and localise games that might otherwise never leave their home countries, and how one person’s passion for the peculiar is building bridges between gaming communities across the globe.

Enjoy.

Joe: Hi Ben, welcome to the What If? Blog. Please introduce yourself and let us know what brings you to the world of board games.

Ben: Hi, I’m Ben—though most people in the board game world know me as Mr Ben, mainly because I couldn’t figure out how to change my Discord name during lockdown and it just stuck!

I got into modern board games through Agricola and Discworld: Ankh-Morpork, and things kind of spiralled from there. These days, I run www.travel-games.co.uk, a little indie shop that focuses on small-box, imported, and under-the-radar games. I also publish and design games—I’m doing my best to encourage others to design and build their own games too.

Joe: Great, welcome. Tell us a bit about the genesis of Travel-Games. What made you take the step into selling the undiscovered?

Ben: Travel-Games began as a mix of impulse and escape. I was stuck in a job that felt increasingly tenuous and pretty awful for my mental health. When my nth short-term contract came up for renewal yet again, I made the decision not to sign it—and to try something different instead.

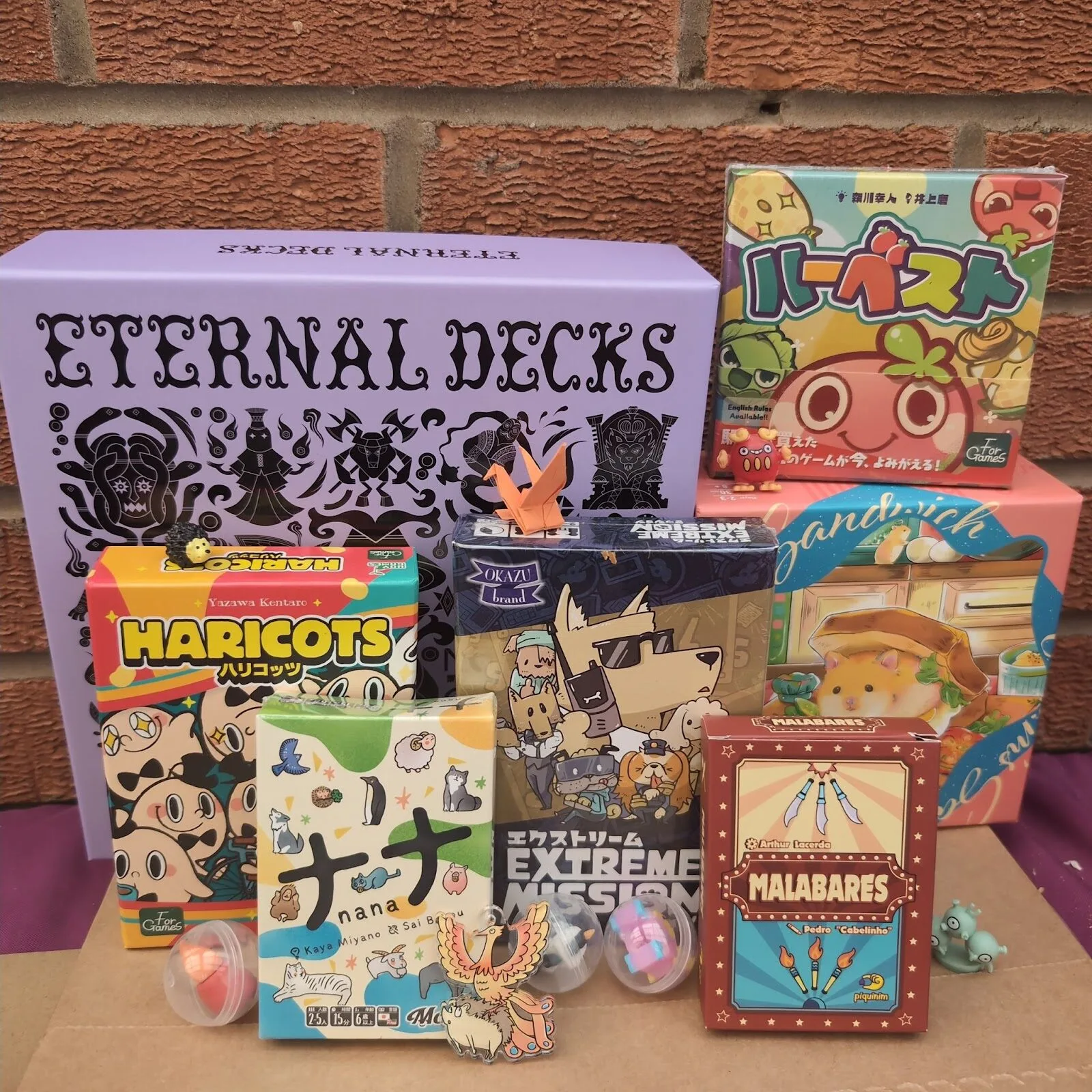

I’d been importing small-box games for myself for years, so I started a store built around that idea: compact, travel-friendly games, great service, and the feel of an indie record shop I grew up going to on my way home from my Saturday job as a teenager. I added a few of my favourite Japanese and indie imports to the shop just for fun—I didn’t think anyone else would be interested. But they sold out on day one, and I quickly realised there was a real hunger for the strange, creative, and hard-to-find titles that often never leave their home countries. Soon after, I signed the incredible Boast or Nothing for publishing, and that’s how the publishing part of Travel Games began.

There was a real hunger for the strange, creative, and hard-to-find titles that often never leave their home countries.

It’s definitely not the easiest route—there’s no central catalogue, and you have to handle everything from translation to customs paperwork—but it’s been incredibly rewarding. I get to introduce people to some of the most inventive games being made anywhere in the world. I’m glad to say it’s more sociable than I ever imagined.

Joe: Impulse + Escape = Something wonderful. Your store brings games to UK gamers that they wouldn’t find anywhere else, and that’s brilliant.

If many games are imports, how do you go about finding them and working out if they are worth importing?

Ben: I keep a close eye on country-specific conventions, especially those that focus on indie design. Tokyo Game Market is the big one—it’s a goldmine for creative, small print-run designs you won’t find elsewhere, or sometimes ever again.

There’s a fairly common misconception that Japanese game designers are somehow “better” than those elsewhere. I don’t really think that’s true—they’re not better or worse. What is different is the lens you’re viewing them through. The games that make it over here have already been carefully filtered and curated—importing is expensive, and translation is time-consuming. So the really rough or unexciting games usually don’t make the cut. What you see is cherry-picked, and that can skew perception.

Most of these games aren’t designed to land a publishing deal—they’re made as personal, creative projects, often to play with friends.

As for how I decide what to import, it’s a mix of things. I read the rules where I can, proxy the game if possible, and watch gameplay videos—even in other languages. There are certain designers I follow closely, and some I’ve developed friendships with over the years. They have a great track record, so I trust their designs. I also have friends in the hobby whose tastes I really value. And sometimes, a game idea just sparks joy or makes me laugh—and that’s often enough, often it has unusual components like plasticine!

Joe: Can we explore that concept of different countries or cultures creating “types” or “styles” of game? An obvious one is Japan, so curation aside, is this a “style” you could outline for us? Follow-up question: where else are your imports coming from?

Ben: Definitely. Japan has a really distinctive game design culture—and a lot of it centres around Tokyo Game Market (TGM), which is a huge showcase for indie and hobbyist creators. A big part of what defines the “Japanese style” is this DIY spirit. Many designers make games in tiny batches, often at home, with limited components: think business cards instead of standard playing cards, ziplock bags instead of boxes, and small print runs of 50–100 copies. There’s even a special area at TGM called Chuck Bag Alley, where every game must be in a baggie!

What’s really striking is that most of these games aren’t designed to land a publishing deal—they’re made as personal, creative projects, often to play with friends or share with the local board game community. That makes for bold, inventive designs that don’t feel bound by commercial expectations. They might not be perfectly balanced or have the most polish, but that’s what makes them interesting. You see a lot of clever trick-taking, climbing, or shedding games (millionaire games), but also really unusual formats and themes that would be hard to mass-produce. It’s a vibrant, eccentric design scene—and that’s what makes it so exciting to explore.

Joe: And where else are your imports coming from?

Ben: Honestly, anywhere interesting games are being made! Besides Japan, I regularly import from Brazil, Chile, South Korea, Singapore, the US, and across Europe. Brazil and Korea both have growing indie scenes that share some of Japan’s experimental energy—smaller print runs, unique mechanics, lots of personal flair. And with indie markets now popping up in the US and even here in the UK (HamishCon), I’ve been bringing in more games from Western designers too. The creativity is everywhere—it’s just a matter of finding it and encouraging it. I’ve been very open about my designs, good and bad as they are, as they’re developed in the Travel-Games Discord, and I think giving a window into the process and showing that not every idea works—but it might make it into a later design—is important.

The creativity is everywhere—it’s just a matter of finding it and encouraging it.

Joe: That’s so cool. I love that it’s about the creativity over profit/publishing.

Can you showcase a recent example that you’ve had into the web store? What caught your eye about it, and what’s different?

Ben: Two recent favourites really sum up what I love about the indie import scene: Compress by Jun Sasaki (from Oink Games) and Mr Pai Pai by Macoto Nakamura.

Compress looks like a minimalist memory game at first glance—just cards showing 1s and 0s in black or white. But once you start playing, it reveals itself as something much cleverer. On your turn, you have to recite the ever-growing sequence of numbers in the deck, in order. Sounds simple—until you realise your only tool is your hand of eight cards made up of 1s and 0s. You’re not just remembering—you’re building a system of notation and compression using your hand. A black 1 might mean “two 1s in a row.” Rotating a card 90 degrees might mean “it’s a zero even though it’s a one.” The game doesn’t tell you how to take notes—that’s the puzzle. It’s part memory, part coding, part pure panic. And you only have two lives.

Mr Pai Pai goes the other way—full chaos and laughter. It’s literally 36 plain white cards in a box. Most of them are secretly glued together in pairs. You dump the whole lot on the table, smoosh them around, and try to pick out the few single cards hidden among them. If you grab a glued pair—too bad! Throw it back and let the next person try. Once all the single cards are found, the player with the most wins. It’s completely ridiculous and always hilarious—watching people try to be delicate or overthink a game that’s basically “reverse card Jenga” is a joy.

Both games are great examples of why I love doing this: minimalist production, off-the-wall concepts, and a play experience that surprises people every time.

Joe: They both sound intriguing. I love that you’re bringing new stuff to the UK market. As a designer of games, getting more ideas from new places is brilliant.

You mentioned your Discord. How are you using that online space to support the shop and your own games?

Ben: The Discord design channel started as a casual place to post design ideas and playtest notes in real time—partly to document the process, but also to show that not every game makes it to the finish line. Some end up in the “spare parts” pile to be recycled into something else later. Others are just… bobbins. I think sharing those ups and downs helps demystify the design process and makes it more approachable and familiar.

I think sharing those ups and downs helps demystify the design process and makes it more approachable and familiar.

What’s been really lovely is that it’s encouraged others to do the same. There’s a little playtesting community growing in there now, with people bouncing around ideas, sharing prototypes, and asking for feedback. It’s exactly the kind of creative exchange I hoped for.

Personally, I have quite an unusual design style—a bit of a blitz approach. Thanks to my ADHD and dyslexia coping strategies, I work very fast and intensely: if I have an idea, I make it immediately. I have a wide range of proxy decks, blank cards, poker decks, and marker pens to hand. Posting in Discord helps keep that momentum going and gives me an outlet to share rough builds and wild concepts as they happen.

We’re also organising a mini Game Market at HamishCon, and it’s been brilliant to see people signing up to bring their designs to share and sell. I’m helping out with layouts, print advice, and general encouragement. The goal is to build something with a similar spirit to Tokyo Game Market—fun, DIY, and community-first.

Joe: The game market sounds really cool. Can you tell me a bit more about it and what you’re looking to achieve?

Ben: The goal is to make game design feel approachable and fun. A lot of people think you need expensive tools, years of experience, or a big budget to make a game—but you really don’t. Most of my prototypes are made using simple tools like PowerPoint and Paint.net. For titles I’m releasing properly through Travel Games (Rotisserie Tricken, Best of Neapolitan, After You Betobeto-san, Dot & Dash: Over and Out), I’ll use something like Affinity Designer—but you don’t have to dive in at the deep end to start creating.

The Game Market is about breaking down those perceived barriers, encouraging people to make something, share it, and just enjoy the process. If you walk away with a playable prototype, fantastic. If you leave with new ideas and some laughs, I think that’s a win too.

Joe: Fantastic. Let’s round this off. What have you got on the horizon that you’re excited about? Any new games coming out, or something that you’re working on?

Ben: There’s a lot bubbling away at the moment—both localisations and my own designs.

For localisations, the big one is Best of Neapolitan, co-published with Portland Game Collective. It’s a retheme of the excellent trick-taker Boast or Nothing, with a twist of my own included—a variant that plays around with the pass cards.

Then there’s Rotisserie Tricken, a nine-card trick-taker where each card acts as four different cards, so the whole game effectively runs on just nine. The rest of the deck is made up of scoreboards, bid markers, and so on—plus there’s going to be a very cool spinning coin as part of the Kickstarter.

Shochikubi is another one I’m excited about: a trick-taking, auction, and set-collection hybrid built around a quality ranking system from Japan and China. That’s releasing at Tokyo Game Market this autumn, and I’ve done all the artwork myself.

Looking ahead to spring Game Market, there’s After You, Betobeto-san—a 1 vs 3 asymmetrical trick-taker with a weird drafting system. The artwork has just come in and it looks incredible. I’ve also written a short story to accompany it, based on the yokai that inspired the design.

On the lighter side, Butt Radio came out of an impromptu game jam at UKGE with Mike (Huff No More) and Dave, after the tannoy kept announcing that someone was sitting on the radio and blocking communications. It’s as silly as it sounds, and it makes me laugh every time it hits the table.

And then there’s Dot and Dash: Over and Out, a climbing game with a poker-hand feel. It uses Morse code as the structure for melds, so the word you pick each round dictates what you can play—which creates some really fun constraints and surprises.

Beyond that, I’ve also got a few special projects lined up for HamishCon in November, our first ever Travel Games convention and indie Game Market. I’m working on a team-based trick-taker about smashing and collecting ceramics, plus I’m handling the artwork for another designer’s game that will be a surprise reveal at the con.

So—lots happening, and hopefully something for everyone.

Joe: Finally, where can we find your stall and your socials?

Ben: You can find the shop online at www.travel-games.co.uk, and our first Kickstarter prelaunch page for Rotisserie Tricken at https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/travel-games/rotisserie-tricken.

I’m also on Instagram at @travel-games.co.uk and on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100093095255023.

And if you’d like to chat about unusual imported games, share ideas, or join in on playtesting, we’ve got a really welcoming Discord community you can hop into: discord.gg/FWAT3AKjaJ.

Ben’s passion for the unconventional and his dedication to supporting indie designers worldwide offers a refreshing perspective on what the board gaming hobby can be. Through Travel-Games, he’s not just importing products but building cultural bridges, fostering creativity, and proving that the most innovative ideas often come from the most unexpected places. Whether it’s a nine-card trick-taker that redefines efficiency, a memory game that doubles as a coding puzzle, or literally just cards glued together for maximum chaos, Ben reminds us that great game design knows no borders.

Thank you to Ben for sharing his insights and for all the work he does to bring these hidden treasures to our tables. If you’re inspired to explore the weird and wonderful world of indie imports, or even try your hand at designing something yourself, you know where to find him.

Oh yeah, and remember to subscribe, if you haven’t already!