Last week I spent a week working for the charity ATE (the Active Training in Educational Trust), directing a Superweek. ATE are experts in play, with over 60 years of experience creating fun and empowering spaces for children and grown-ups alike. They provide educational holidays that focus on building confidence, developing social skills, and creating lasting friendships through adventure and play.

A Superweek is a summer camp experience for children aged 8 to 14. These residential camps combine outdoor adventures, creative activities, and collaborative games, all designed to help young people discover new skills and build resilience in a supportive environment.

As a Director of these Superweeks, each evening we put on an evening activity. Those activities are often games focused around play: we might do a big game of battleships, lots of little games and competitions, races, that kind of thing. ATE’s approach centres on the belief that play is fundamental to learning and personal development, so these evening activities aren’t just entertainment but opportunities for growth and connection.

I was really keen to explore taking a board game concept and turning it into something that would be a live event played out over about an hour and a half of the evening.

I’d been wondering for a while what would happen if you took something like a worker placement game, but instead of using meeples as your workers, you could use people as your workers. A live action board game? Imagine Giant Snakes and Ladders played by people, but instead we’re looking at a worker placement game (cos snakes and ladders is shit).

This blog post explores what I learned from that process: how it came about, what the actual game was, and what it tells me about game design.

The Genesis of an Idea

A few weeks previously, a friend of mine had moved house and had a lot of boxes. I’d also seen on Instagram a quirky little video where you can make a caterpillar truck car out of boxes.

Both of these bits came together and started me thinking about boxes and how I might take a load of used cardboard boxes to summer camp. As I was experimenting with ideas (whilst moving boxes from my car – 40 boxes is a lot!), the thought came to me that there must be people who make these boxes, and they must work in a box factory. I wondered what that might be like.

That was the initial genesis of the idea: what would happen in a box factory?

What would happen in a box factory?

A lot of the games we play in the evenings are structured around characters and performance. You might be playing battleships, but you’d have the leader of the fleet dressed up, organising the battleships. There’s always some element of performance art to these activities. The box idea ended up becoming this worker placement game that I designed in an afternoon. A worker from the box factory needed help to fulfil an order, and would this group of children be able to help (we can ignore child labour laws if we’re playing a game, right?!).

Designing something in an afternoon with real time pressure that needs to be playable by the end of the day puts enormous constraints on what you can do and what you can expect from the game. It leads to quick choices, with little time to deal with anything that doesn’t quite work. Let’s think a little about the game…

The Game Itself

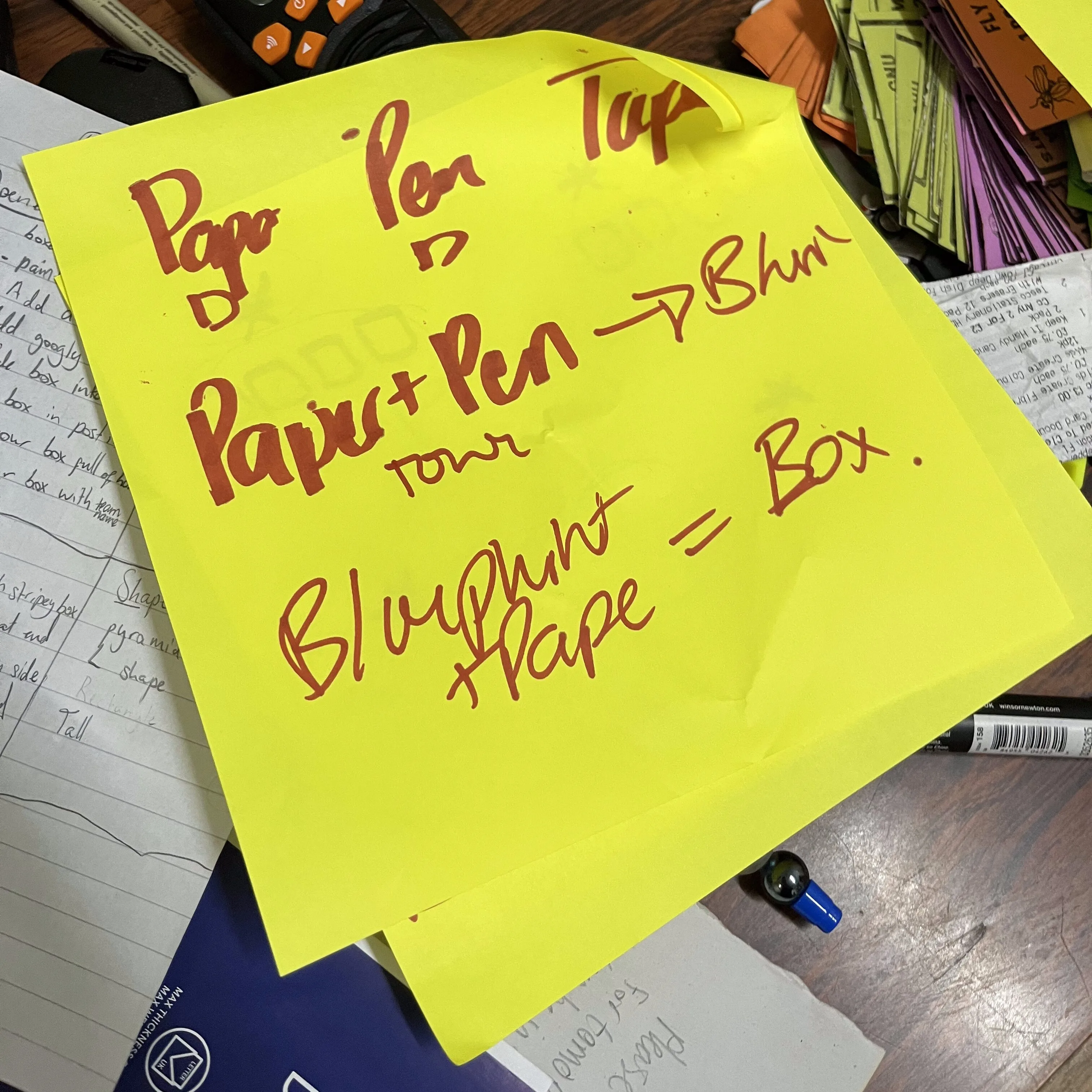

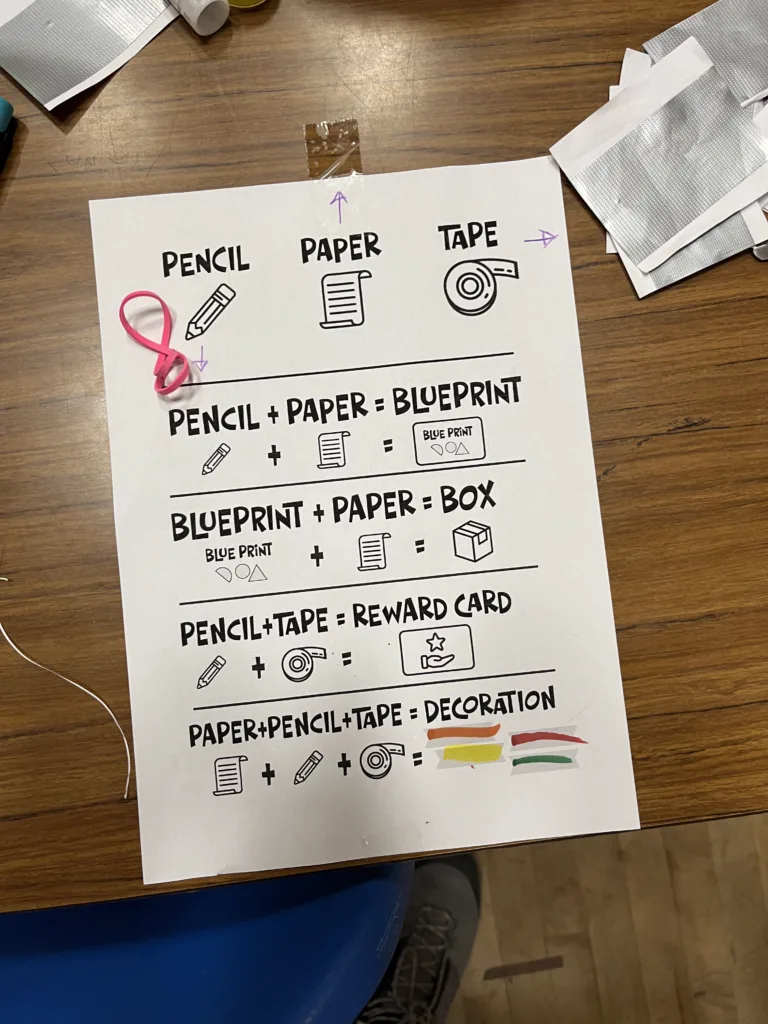

The game was fairly straightforward. There were three basic resources: paper, pencil, and tape. Each team (seven teams altogether with about eight people in each, led by an adult) would put out one or two of their workers (actual people!) each turn to decide which resources they were going to get.

Workers would go and sit in chairs with big signs around the room. I was at the front managing like a factory floor. They would grab their resource, be given it by another adult managing that station, and take it back to their team. They had a menu that told them how those resources worked together.

It was fairly simple in terms of worker placement, resource management, and crafting elements. If you took your pencil and a piece of paper to the blueprint station, you could pick up a blueprint, getting you one step closer to a box. If you took a blueprint and a pencil to the box station, you could pick up a box (maximum of four boxes).

Using different combinations of materials, every time you placed workers out, you could get blueprints, paper, pencil, tape, but also colours to decorate your boxes with: four different colours (red, blue, green, yellow). You could also pick up challenge cards for end game scoring.

It was fairly simple in terms of worker placement, resource management, and crafting elements.

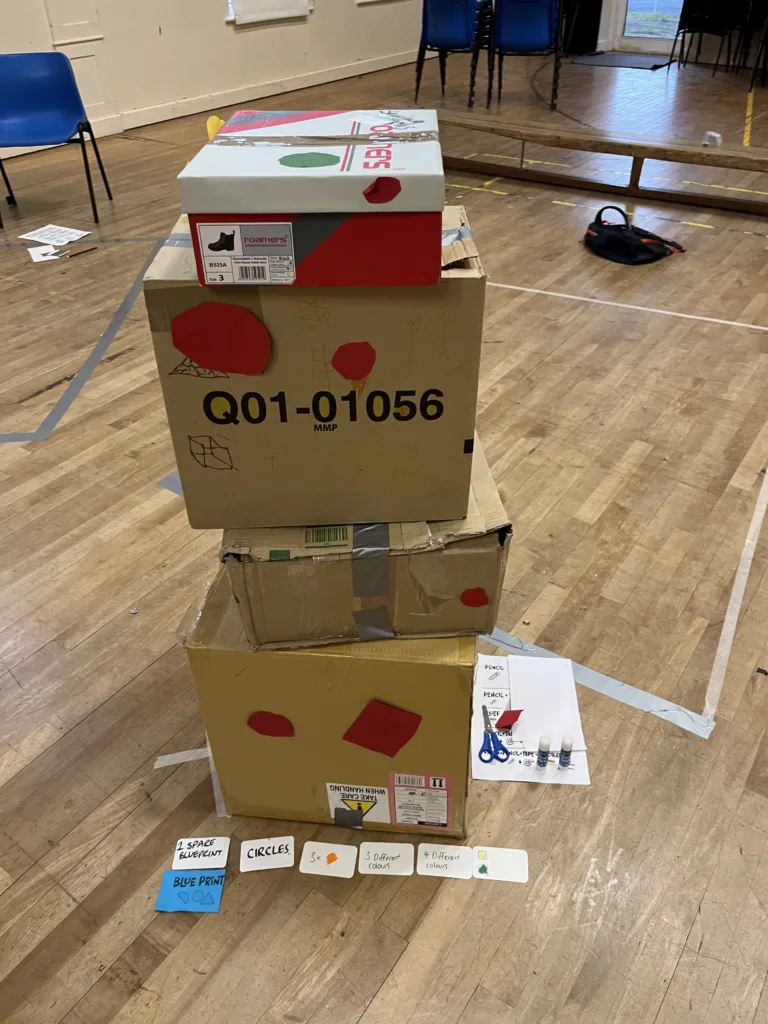

The idea was that over about an hour’s worth of rounds, you would build a tower of four boxes, decorate each face with colours, and then score points based on challenge cards. A challenge card might say ‘one point if there’s a blue box next to a red box’. So you have this interesting pattern puzzle where you have point scoring cards and need to decide how to decorate your boxes to maximise points.

The Experience

The game played for maybe ten rounds with some theatrical elements. You’d send your workers out, there was a pause, then workers returned. We did rest breaks where they had to do exercises, pretending they were resting in the factory. Once the final team had placed their fourth box, we triggered the end of the game.

It went really well. For quite a lot of people, it was their first time playing a worker placement game at all, as these aren’t board game people. They’re just an audience of kids and adults drawn from the general population. Those who did recognise the worker placement element really enjoyed the live action aspect and the multiple different puzzles throughout.

Lessons in Rapid Design

Planning in just one afternoon meant I needed speed and simplicity. This was important because each team was led by an adult who had to understand the game quickly without much opportunity to ask questions. However, one of the bigger challenges was the scoring mechanism. Whilst people understood building the boxes, I didn’t explain the scoring well, mostly because i didn’t understand the scoring myself when the game began. We mitigated this by going around and talking to different groups about their choices.

Here’s where designing in an afternoon breaks down: there’s no opportunity to balance, so your first guess has to be your best guess; your first play-through is the only play-through. When we looked at end game scoring, most groups scored around 20 points, but one group scored around 50 because they’d worked out a particular way to maximise points.

The scoring was wildly unbalanced. However, in our scenario (a game only ever to be played once, a one time live action experience), that really didn’t matter. If I’d spent lots of time working out the scoring mechanism, I would never have finished the thing.

Key Takeaways

This points to something important in my board game design: stop worrying about making a good game, and just make a game. Don’t worry about the bits that are unbalanced. I tend to worry about that too much. Make something playable quickly, then work on balancing later. The phrase “perfect is the enemy of good” springs to mind.

Perfect is the enemy of good.

Anon.

The idea of live action board games is really interesting and fun. Looking around the room, all 43 children were highly engaged. The adults found it slightly stressful managing their teams and the rather overcomplicated scoring system, but I scored everything up the next morning by walking around and carefully examining their towers.

Designing games at pace is good for me because it forces me to create something quickly. Things like balancing can happen later: make the thing first. This is a common adage across all design, and I think that’s my big takeaway. When an idea comes, roll with it and don’t worry, let it happen. You end up doing some quite wonderful things.

Final Thoughts

If you’re interested in finding out more about the summer camps, you can find information about ATE online here. I’ve also got a video rundown of the game on Instagram if you want to see it in action.

I’d love to discuss the game in more detail with anyone interested, particularly the design challenges and solutions. Sometimes the constraints of real world application teach us more about design than endless theorising ever could.

What’s next – I’ll make this into a “my first worker placement game” for my kids and see where it goes from there!

This looks pretty awesome and fun!